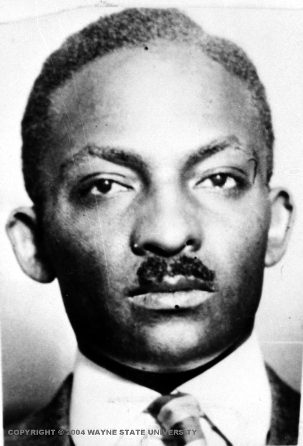

Dr. Ossian Sweet

Dr. Sweet, from Wayne State University's Walter P. Reuther Collection.

Born in Florida, Dr. Sweet graduated from Howard University College of Medicine before becoming a doctor in an overpopulated Black Bottom neighborhood in 1921; he met his wife-to-be, Gladys Mitchell, in 1922, and in 1923, after they were married, he finished his medical education in Vienna and Paris (Bourbeau). Returning to Detroit with his wife and baby Iva (Speedy, The Chicago Defender, 1925), he took a house on Garland Street in an all-white neighborhood in September 1925. Knowing there would be mobs, Dr. Sweet, his brother Henry, and several other friends stocked the house with ammunition as a defensive measure. Though police were stationed outside the house, they did not interfere as a racist white mob of 400-500 (The Detroit News) from the Waterworks Park Improvement Association threw stones at the house on the second night (Bourbeau). Shots were fired from the house in defense and killed one of the whites, Leon Briener, that night on September 9, 1925 (Speedy, The Chicago Defender, 1926). As a result, Dr. Sweet, Gladys Sweet, his brother Henry Sweet, and others who helped defend the Sweet family -- Dr. Otis Sweet, Leonard Morse, Hewitt Watson, Joe Mack, Norris Murray, Charles Washington, John Latting, and W.E. Davis (Speedy, The Chicago Defender, 1925) -- were arrested for murder.

“I had hoped to have a home for my baby,” said Dr. Sweet in 1925, “a place where she could attend school and her environments would be healthy and helpful. It was for her sake that my wife and I determined to sacrifice many things in life so that our little one would have the best advantages possible” (Speedy, The Chicago Defender, 1925).

Behind the scenes, Black Bottom’s Rev. Robert Bradby, whose teaching “protect your home at all cost” impacted Dr. Sweet heavily, worked with the NAACP around the clock to ensure the Sweet family’s freedom (Poston, The Pittsburgh Courier). It was almost two years before the charges against the Sweets were dismissed.

The case prompted nationwide outcry from Black communities, with the Afro-American displaying headlines such as, “Eyes Of Country On Sweet Case In Detroit” in November of that year. Gladys Sweet recounted her horrible experiences in jail to the Pittsburgh Courier. Clarence Darrow was selected by the NAACP as defense lawyer; he took the case for a small fee (Bourbeau). According to NAACP activist and professor William Pickens, writing in the Afro-American, the white witnesses were probed into “to find the root of that cancer of race-hatred, of inhumanity, of brutal prejudice.” The actions and statements of the white witnesses boiled down to racism, nothing more.

Despite this, the first trial resulted in a hung jury, though the Sweets were cheered and welcomed at centers like Mt. Olivet Baptist Church in January 1926 (Brown, The New York Amsterdam News). Henry Sweet was acquitted by an all-white jury in May (The Washington Post) and a year later, in July 1927, The Chicago Defender reported that Dr. Sweet, Gladys Sweet, and the eight acquaintances who helped the family that night were set free.

Sadly, the Sweet family’s life took a turn for the worse after that. Gladys contracted tuberculosis while in jail, passed it onto their infant daughter Iva, and both died in 1928 when Gladys was 27; Dr. Sweet’s career and mental health never recovered and he committed suicide in 1960 (Bourbeau).

The Sweet case is a stark example of how racism and hatred constricts and destroys Black families and communities. Moreover, it is a reminder of how far the police’s and the justice system’s reinforcement of racism can reach.

See also: A Legacy of Housing Discrimination

Tags

Sources

Bourbeau, Heather. “Dr. Ossian Sweet’s Black Life Mattered.” JStor Daily. June 17, 2015. Accessed Aug. 22, 2020.

Brown, Warren. “Dr. and Mrs. Sweet Cheered.” The New York Amsterdam News. Jan. 6, 1926, pp. 1, 3.

“Dr. Sweet and Eight Others Win Freedom.” The Chicago Defender. Jul. 30, 1927, pp. 1, 8.

“Eyes of Country on Sweet Case in Detroit.” The Baltimore Afro-American. Nov. 14, 1925, p. 1.

“Henry Sweet Cleared in Race Disturbance.” The Washington Post. May 14, 1926, p. 3.

“‘I have to die a man or live a coward’ -- the saga of Dr. Ossian Sweet.” The Detroit News. Feb. 11, 2001. Accessed Aug. 23, 2020.

“Mrs. Sweet Tells Tragic Story Of Lonely Hours in Detroit Jail, As She Waited, Helpless, For Aid.” The Pittsburgh Courier. Nov. 7, 1925.

Pickens, William. “Darrow Makes Sweet Trial Great ‘Human Show’.” The Baltimore Afro-American. Nov. 14, 1925, p. 1.

Poston, U.S. “‘Bradby Saved Negro in Detroit,’ Says U.S. Poston.” The Pittsburgh Courier. Nov. 19, 1927, p. 2.

Speedy, Nettie George. “Darrow Traps Witnesses in Sweet Case.” The Chicago Defender. May 8, 1926, pp. 1, 4.

Speedy, Nettie George. “Jury Disagrees on Sweet Case Verdict.” The Chicago Defender. Dec. 5, 1925, pp. 1, 3.